justing.net

On Looking by Horowitz, part 2

This is the second part of my raw reading notes from the book. See also the first part, and the final part.

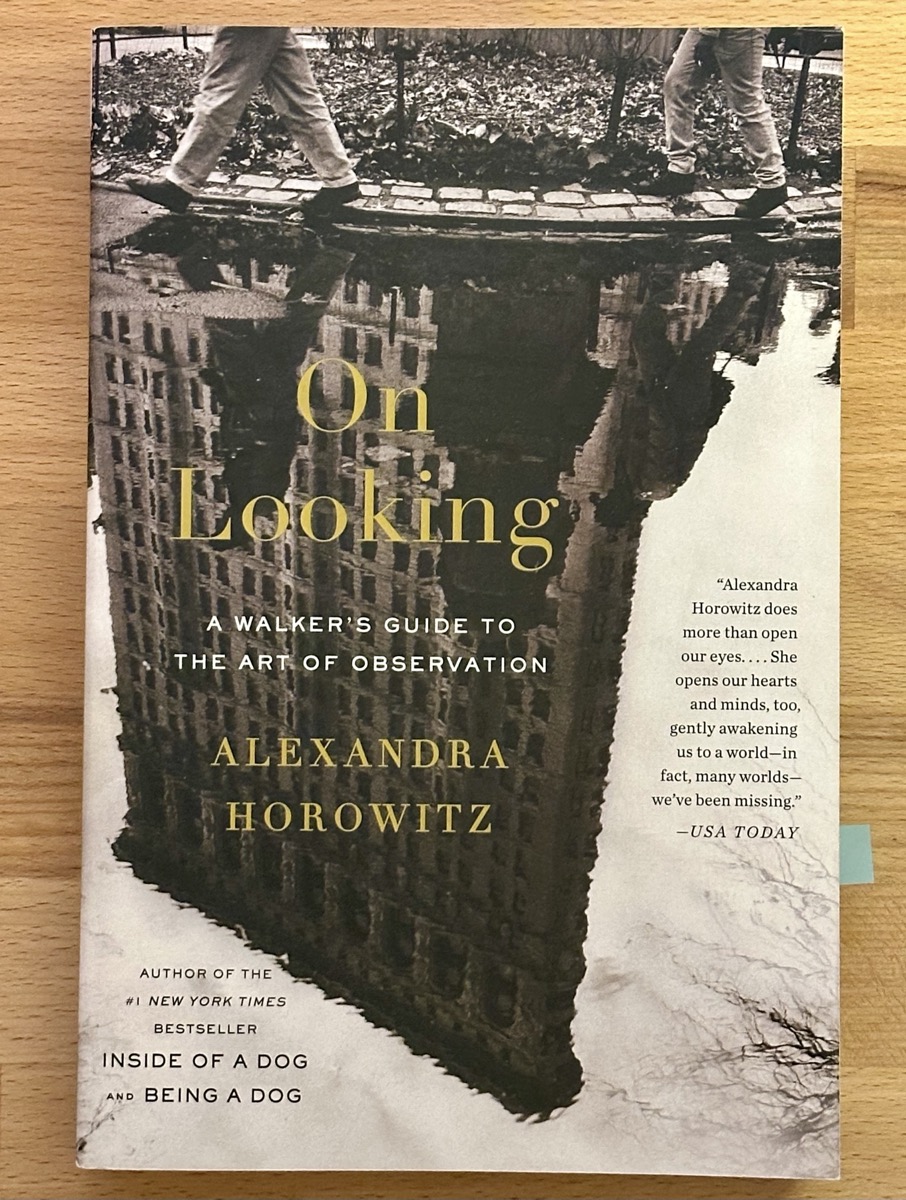

“On Looking, a walker’s guide to the art of observation” by Alexandra Horowitz, 2013

I am reading the Scribner paperback, 1st ed. 2014.

This is the 15th book that I’ve read this year.

Chapter 5

Ch 5 is about insect sign. So much of this chapter applied beyond just spotting insects and their signs. “Half of tracking is knowing where to look, and the other half is looking.” This feels like a gentle introduction, literally introducing the very most basic skill, for accessing more of my bioregion. On my next walk along the trail, I’ll surely be stopping at every tree and leaf, every cement block.

- 94: Street pigeons are vilified? By whom? I like them.

- 98: Insects species are paired up with plant species. Or insects have preference for only some plant species.

- 102: Invasive plants don’t get paired up with native insects, so they’re usually left alone, and so they grow better.

- 106: Look closely at slug traces, you will see the parallel lines from their teeth (radula) in those traces. What about snails?

- 109: We see what we look for, and don’t see what we don’t look for. Uexküll again describes an incident of looking for a pitcher of water and not finding it on his table. It was clay pitcher that he searched for, but the table had a glass one.1

- 111: “Half of tracking is knowing where to look, and the other half is looking.” -Susan Morse

- 111: “A small bit of knowledge goes a long way when thinking about where to look.” I want this list of small bits of knowledge.

This last one is probably the key insight of this chapter.

Chapter 6

Ch 6 is about urban animals. Not many of the creatures made an appearance; they are usually out at night. But some clues were offered to see their evidences and preferred shelters.

- 120: The sizes of holes and spaces that some rodents can fit into: raccoons, 4 inches; squirrels, a quarter coin; mice, a dime. These are quite small.

- 122: We see what we expect to see, when we have an expectation. It is difficult to turn off this filter for the expected. We simply don’t notice what we aren’t looking for. “expectation is the lost cousin of attention.”

- 126: Animals that are just hanging out, in the posture of loitering, they are known to be “loafing” by the experts.

- 127: Thigmo- = touch. Thigmotaxic/thigmophilic = touch-no-likey/touch-likey.

- 135: The “urban cliff hypothesis:” that the common urban animals (rats, pigeons, mice, bats, and also plants) co-evolved with us from our cliff dwelling past to our current manufactured cliff-like urban environments.

- 136: People’s preferences are to have the front door set back a bit, and up a bit above ground level. This is similar to a cliff cave entrance.

- 136: Sound punctuates the beginnings and ends of events. Without it there is neither of these and can feel like “a little peak at infinity.”

Chapter 7

Ch 7 is about the experience of walking on urban streets. I’m very much getting the sense that this is a quite NYC centric book. There is nothing wrong with that, but there is a lot more to the world than that one particular city. And while it’s true that these 1-inch portrait introductions to these topics are nothing but templates for re-use in other settings, the more your context differs from the very dense urban US setting, the larger the denominator below the portrait becomes. I.e. a 1/8-inch portrait.

That being said, I generally quite enjoyed this chapter and collected quite a few notes.

- 139: “We must always say what we see, but above all and more difficult, we must always see what we see.” -Le Corbusier

- 140: “Time doesn’t matter.”

- 141: The sidewalk may be viewed as a theater, as an improvisational dance, as a kind of show.

- 141: Photograph vender food carts.

- 143: A platoon is a group of walkers that haven’t got any affiliation with each other.

- 144: Who runs the Transportation Research Board? It is one of the seven major branches of the National Academies.

- 146: The rules of flocking behavior: 1) stay close but don’t bump, 2) follow the one in front, and 3) keep up with those next to you. That’s it, those are the rules. See also boids.

- 147: When we do inevitably bump into each other in crowds, we keep our hands close to our own bodies, and our faces turned away. Knowing that we all do this feels like a kind of magic. Is it learned or instinct?

- 149: The book predates widespread smart phone use, it is written in the early middle period, and it shows. See also 150.

- 149: Head motion and angles telegraph where we’re going.

- 151: There is an urban tradition of walking wherever. Or there was until the cars came and tried to take away that tradition.

- 152: The term “jay driver” should keep trying to come in.

- 152: Lots on the act of looking at another person here. To hold in the eyes continuously can mean strong dislike or desire. But it’s also a form of communication, as between walker and driver.

- 152: When you look at someone directly, you influence their choices. They’ll move around you. They’ll relax when you stop looking at them, and maybe sit down then instead of before if they are looking for a seat.

- 153: Hans Monderman’s “naked street” proposal, a place without the safety accessories that forces (let’s say strongly encourages) the users to navigate intentionally. Drachten in The Netherlands has such an intersection.

- 154: Sidewalk glass pavement lights.

- 155: Do you even notice the sidewalk? It’s a sidewalk.

- 157: Breaking the flow symmetry by adding something that people have to walk around, like a pillar, can increase the flow rate of foot traffic.

Chapter 8

Ch 8 is about observing the act of walking itself, on the individual level. It is also about what we may notice of others while they are out and about walking too.

- 170: Over millions of steps, tiny anatomical variations wear into being an acquired deformity. A visible professional deformity? Sometimes (maybe apocrephal).

- 171: Example of a man that refuses to correct his posture because it’s not the posture of a humble man.

- 176: Laënnec invented the stethoscope and compiled a list of disease associated sounds. I want this list. There are some examples listed here. See also references on 286.

That’s it for this installment.

-

Is this a kind of negative visual hallucination? ↑

To Reply: Email me about what you notice.

Posted: in Reading.

Other categories: book-notes.

Back references: none.

Tags that connect: [[Horowitz]] On Looking by Horowitz, part 3, An Imperfect Library of Noticing, On Looking by Horowitz, part 1, Latest Now Page Updates, Latest New Now, Update to Now; [[insects]] Almaden Quicksilver County Park, 2023-10-19: Joshua Tree National Park, 2023-08-26: Pittsburgh, PA; [[On Looking]] On Looking by Horowitz, part 3, An Imperfect Library of Noticing, On Looking by Horowitz, part 1, Latest Now Page Updates, Latest New Now, Update to Now.

Tags only on this post: bioregionalism.