justing.net

On Looking by Horowitz, part 3

This is the final part of my raw reading notes from the book. See also the first part, and the second part.

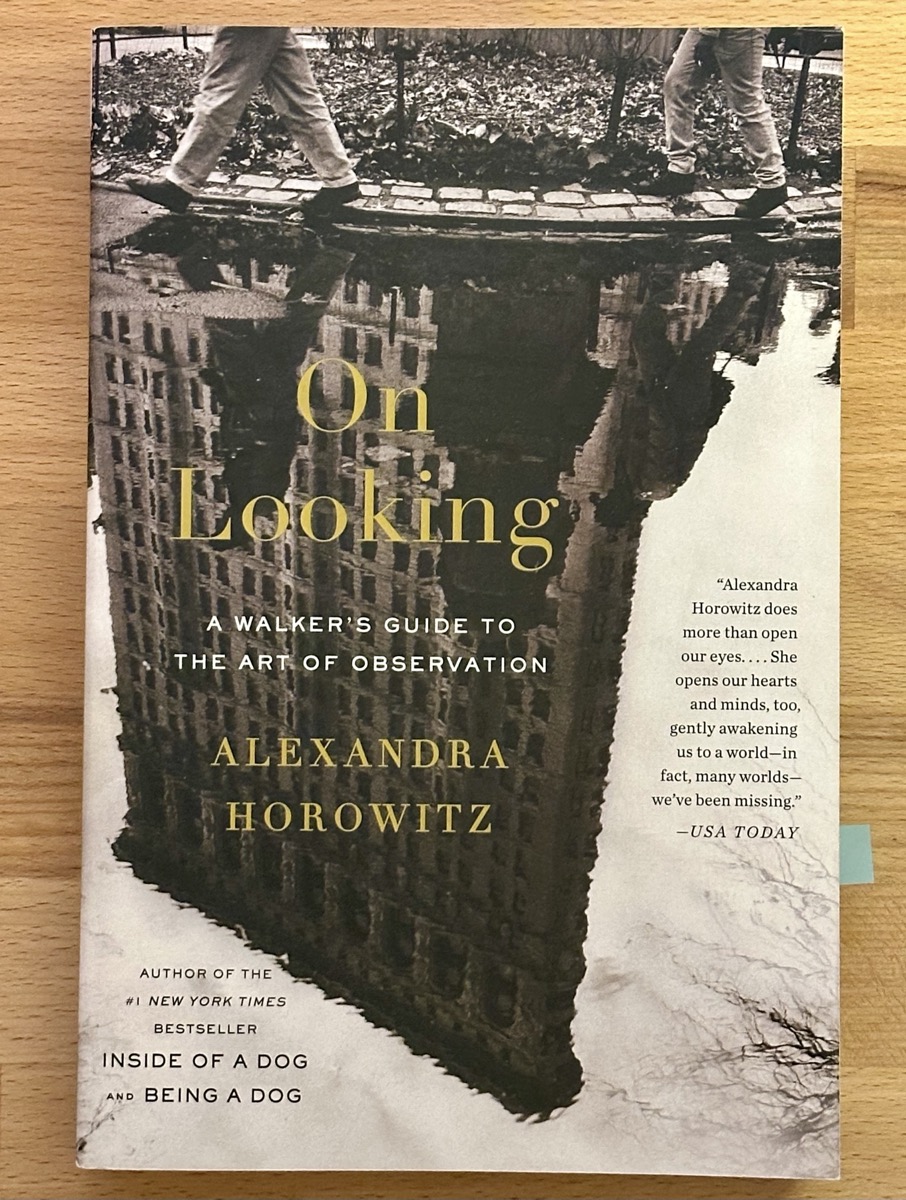

“On Looking, a walker’s guide to the art of observation” by Alexandra Horowitz, 2013

I am reading the Scribner paperback, 1st ed. 2014.

This is the 15th book that I’ve read this year.

Chapter 9

Ch 9 is about walking and seeing without sight, walking with a blind person.

- 188: During normal conversation, people look at each other about one third of the time. The listener is looking at the speaker about twice as much as the other.

- 200: There are brain cells that are specially attuned to our “peripersonal space,” the area within our reach, and they trigger for sight, sounds, and touches. These special cells enable us to perceive when we are being approached stealthily while distracted; we can feel another presence. If we’re paying attention to them.

- 201: A blind person who is well experienced with using a cane, the end of it is mapped onto the these specialized peripersonal cells. Slight bumps and touches to the cane tip are sensed in the same way.

- 208: One plus about the people lost in a conversation on their cell phone is that they are broadcasting their location with all that talking.

Chapter 10

Ch 10 is about attending to sound while out and about. The previous chapter was about the hyper-specialized sound sensitivities of a blind walker. This one is about the more ordinary sonic landscape that is available for us to attend to at any time.

- 212: The sound of an engine idling could be a soothing sound if listened to for itself. It’s steady state and rhythmic.

- 213: Exploiting the wave equation of $v = l \cdot f$ to convert sound frequency into a spatial dimension. A potentially useful insight to exploit for sonic explorations.

- 213: Naming a sound (or any other thing) changes our perspective and experience of it. One pitfall is that we may not hear the sound anymore, we hear what we expect from the name instead and then move on.

- 213: The “safari phenomenon” is to identify the thing that you see or hear, and then simply move on without actually attentively observing the specimen that is before you. You only learn that you were near the thing that you already knew, and nothing else. Pay attention to that thing!

- 215: Having a secret mission to find a particular sound (or, well, anything else) is one way to deepen your experience of paying attention to your surroundings. But kind of selectively.

- 217: “any sound we do not like we call noise”. I’m not entirely sure I agree with that.

- 219: Sounds that we are annoyed by stimulate a reaction similar to other stressful situations. E.g. final exams, lions, etc.

- 219: Ears make their own unique sounds. I suspect this means that they reflect the sounds that are impinging upon them in individually characteristic ways. It could be an individuals specific sonic fingerprint. Keyword: otoacoustic.

- 221: Speed of sound (in air) is 1100 feet per second. Or 330 meters per second.

- 224: Cocktail party effect: the ability to hear your name or a topic you are interested in across the room of talking people. Complementing this matched filter effect for detection is “auditory restoration.” This is when we fill in sounds (or just their information content, but we still perceive it as sounds) that we are unable to detect for all the noises. This is accomplished out of our awareness usually by paying attention to other peoples faces and mouths.1

- 224: It was finally at this point that Horowitz mentions the optic nerve, it seems late for a book on looking at things.

- 224: I thought that “with our eyes open and daytime in front of us” [we can see] was a novel way of putting it.

- 225: Bats are the principle reason that the biting insects aren’t so much of a bother. Yay bats!

- 226: It is not understood (as of 2013) how bats don’t get their own voices confused with all the other bat voices out there, especially when there are a lot of them.2

- 227: Natural sounds that are more self-similar are preferred. Examples: running water, the in the trees. They sound the same at different speeds or volumes, so they are like fractals in that way.

- 227: Attempts have been made to create taxonomy (or typology) of city sounds. Horowitz says there aren’t words to mark all the different sounds.

- 228: People who spend time in the forest are able to identify each type of tree by its species characteristic sounds. I would go further and individual trees are so different that even within species each exemplar is quite possibly identifiable by sound alone.

- 228: The sounds of a place are not static, we may lose the sounds of cars parking as our modes of transportation change. Speculative “Catalog of Lost Sounds.” More speculative: The Catalog of Future Lost Sounds.

- 229: The feeling of sound; low frequencies possess your innards, high frequencies are an unidentifiable presence felt everywhere outside.

- 229: US Government low frequency crowd control / military technology.

- 230: Sound cleanup in films/foley. Only one person walking in a group is often heard. Maybe just one dominates?

- 232: Maybe the world becomes an illusion to some when they disconnect the sounds from the events around them by donning sound isolating headphones.

- 233: 7 Hz is aligned with alpha brain waves, and may cause headaches or nausea.

- 236: Sound waveguides. The sound travels further in a warm layer that is bounded by a cold layer.

Chapter 11

Ch 11 is about noticing smells, with a dog as the walking companion.

- 242: Our sight sense so dominates that we do not conceive of another way to organize the world.

- 244: Does ‘-somatic’ mean smell? As in macrosomatic or microsomatic?

- 245: Dog nose sensitivity is so good that 1 part mustard in a trillion parts hot dog is still detectable. I am imagining the experiment.

- 246: A noticed sound of the flagpole rope jostling or banging in the wind so clearly projected the image of a seaside cottage n New England. It’s a nice image and meta-image. Outer reality/external frame?

- 251: National registry of geodetic survey marks is about the history, and National Geodetic Survey has the current database.

- 251: “Dogs are perfectly culturally ignorant.”

- 253: Some good observational skill displayed about the woman with the dog.

- 253: Similar to the sounds of diseases, there is a set of smells too. Some good descriptions here too.

- 254: Are linden leaves (wikipedia) ever small? Maybe it’s spring time.

- 256: The mammal gate is shoulders and pelvis in opposition (the wobbling sausage), whereas for reptiles are in sync because they move the limbs on one side of their bodies together.

- 257: Horses are very sensitive on the sides of their bellies. It’s how they receive the telepathic signals from their rider.

- 258: Reporting on the dog walk, there is always something to report. Number 1, number 2, at minimum.

Chapter 12

This is the short wrap up chapter, pulling together everything she has learned in the previous 11 chapters.

- 260: A person must become quite nose blind to smell nothing in the city, especially one such as New York. Perhaps she just forgets what she noticed before? She said she didn’t smell anything, I have to accept it.

- 262: Is purple still such a rare color. Thinking about it, I think it might actually be.

- 264: Walking is a mental escape, a change to engage with something else.

- 265: We could pay attention. And we could pay attention more.

I’ll do another post later with a few of my thoughts, reactions, or comments.

-

This is a different “skill” than the one that Henrik is talking about in his article on perception. I mentioned it the other day. ↑

-

My own hypothesis, being a completely uninformed person on the internet, is something like the cocktail effect already mentioned. They know the sound of their own voice well, so they can pick it out from some background confusion. I was going to also say that maybe they can process the direct and reflected sounds of other bats to get a super image. But as I was about to write the idea it started to sound more and more impossible. ↑

To Reply: Email me about what you notice.

Posted: in Reading.

Other categories: book-notes.

Back references: none.

Tags that connect: [[dogs]] Week Notes No. 43: Daily Bits, New to me Facts and Ideas in December 2024; [[Horowitz]] On Looking by Horowitz, part 2, An Imperfect Library of Noticing, On Looking by Horowitz, part 1, Latest Now Page Updates, Latest New Now, Update to Now; [[On Looking]] On Looking by Horowitz, part 2, An Imperfect Library of Noticing, On Looking by Horowitz, part 1, Latest Now Page Updates, Latest New Now, Update to Now.